Arent van Bolten, Monster.

British Museum, London.

Arent van Bolten, Monster.

British Museum, London.

Agostino Veneziano, Dragon and Butterfly.

The Warburg Institute, London.

How did you do? Did you guess correctly? There were some great prognostications for this weird sea serpenty thing, with the thing coming out of its head identified as a blowhole spouting water or an oarfish’s frilly crest.

It’s neither. It’s made of flesh and it’s sticky.

Think you can handle the truth now?

This creature is a Reversus Indicus, an Indian upside-down fish. You probably know if better as the humble remora.

That’s right. This is what a remora looks like in real life.

(Image from Wikipedia)

How did it end up looking like the thing at the top? For a start, the strange fleshy blowholey umbrella coming out of its head is an extremely confused rendition of the remora’s suction disc, as seen below.

(Image from Wikipedia)

Second, it’s derived from an account of fishing using remoras (specifically that of Christopher Columbus, itself probably spurious). Remoras have historically been leashed with ropes and sent to adhere to fish or turtles. Then all you have to do is reel ’em in! But somewhere along the line this “hunter fish” got interpreted as this big eel aggressively seizing other sea creatures. Notice how it’s sticking to a seal, and there’s a sea turtle nearby (it’s next).

(Image from Arkive)

And, of course, since remoras often stick upside down to other animals and have generally weird anatomy, we ended up with the reversus, the reversed fish.

Moral of the story is never underestimate just how much people can get confused about an animal’s appearance.

What do you think this creature is? Yes, it’s a real animal that got lost in translation.

From Ulyssis Aldrovandi’s Natural History.

The Dictionnaire Infernal‘s Cerberus is a dandy fellow.

Hello again! Here’s the solutions to the Ortus Sanitatis Quiz. How did you do? Judging by the responses, not too many people were eager to hazard a guess, but that’s fine, here’s where you get to see that you were right all along.

First up is one of the dreaded gold-digging ants. You’d think they’d know by then what ants look like, but their large size seems to have discombobulated many contemporary authors into depicting them as vertebrates of some sort.

Another animal that a lot of bestiaries got confused about was the chameleon. If you’ve never seen a chameleon before – hell, if you’ve never seen a lizard before – it’s probably hard to picture it. Some figured that, going by its name, it’s some sort of camel-lion hybrid. Or a griffinesque thing, who knows? Chameleons are weird.

This one’s easier. The spots and fragrant breath identify it as a panther.

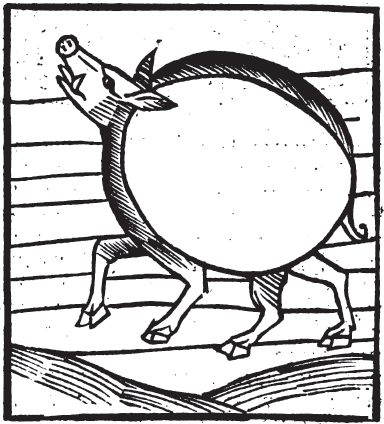

And the fire wreathing this piglike thing clearly sets it apart as a salamander.

“What’s a scorpion like? It’s got… a sting on its tail right? But what’s the rest like? Eh, who cares”.

This baffling bird is a caprimulgus, goatsucker, or nightjar. The authors of the Ortus Sanitatis figured it needed some way to dispense its stolen milk. And in fact…

… this one’s also a nightjar! Trick question, I included two goatsuckers. This one shows it in the actual act of feeding on a nonplussed goat.

This one’s easy. Stag beetle! Or Vikavolt, who knows.

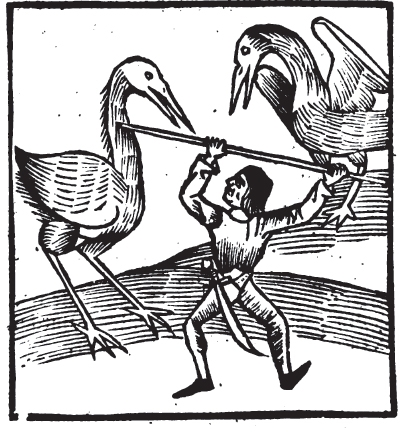

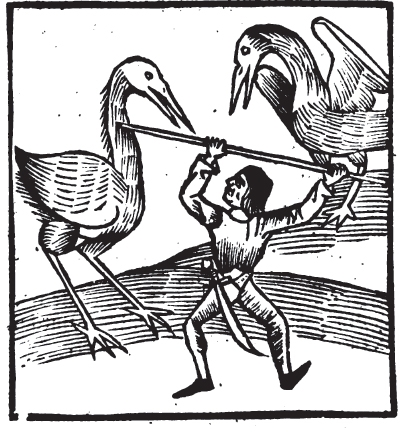

And those aren’t giant birds, they’re cranes fighting a pygmy.

The lagopus, “rabbit foot”, is more commonly called the ptarmigan today. But the authors figured that a rabbit-footed bird probably had more rabbit to it than that.

This one’s tricky. It’s an opimachus, or “snake fighter”. The term originally referred to a type of insect, but here I think there was some confusion with the secretary bird.

Is this the origin of the opinicus? I do believe so!

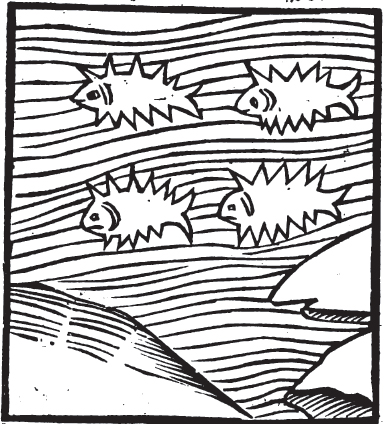

Insects going in and out of a fire? Pyrallis, obviously.

An ostrich is a struthiocamelus. That means it’s part camel, right? A camel-bird. Yeah. A camel-bird. With wings. That can’t fly.

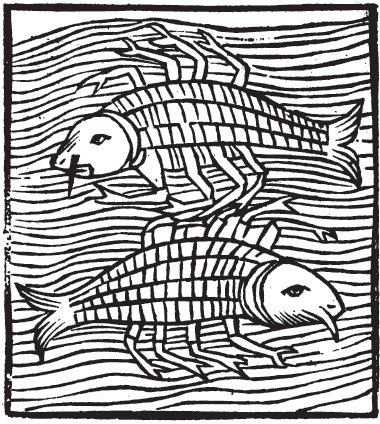

Something tells me the artist never saw a dolphin before.

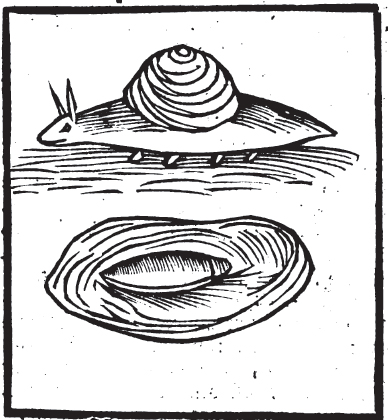

Or an oyster.

Or an octopus. See, the ancient Greeks (for instance) knew what a polypus looked like because they fished it up and ate it. But get yourself a landlocked medieval European and tell them that there’s a sea creature with eight legs… well, it’s a fish right?

Starfish are also fish.

“Turtles are animals with shells? The only thing I know that has a shell is a snail… so… it’s a snail with legs?”

Giant tortoises are delicious.

And finally, everyone’s favorite river-horse, the hippopotamus. Someone took the horse part a bit too literally.

How did you do? Give yourself a pat on the back if you knew at least half of them!

Come one, come all! Step right up and take the ABC Ortus Sanitatis Quiz! Amaze your friends – mystify your enemies with your encyclopedic knowledge of creatures!

The rules are simple. Presented and numbered here are twenty (20) unretouched creatures from the pages of the Ortus Sanitatis. Your task, should you choose to accept it, is to identify them all. Some are laughably easy. Some are fiendishly difficult. Some are trick questions. Which is which?

If you already know the solution because you’ve read the Ortus Sanitatis, don’t spoil it for other readers! A detailed analysis of the answers will be posted later. Have fun [sic]!

1

1

2

2

3

3

4

4

5

5

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

“Now wait a darn minute!” you may find yourself asking. “The Freybug isn’t a modern monster, even if it’s obscure. It’s the Norfolk black dog. It got itself a starring role in William O’Connor’s Dracopedia series (which you should review) and even got name-checked as a Hound in Final Fantasy (pictured). It even got its own Wikipedia entry!” You’d be right as usual, good reader. But I would like to draw attention to the dearth of information regarding this Freybug. What is it? Where did it come from? Why was it used in the Dracopedia and Final Fantasy?

“Now wait a darn minute!” you may find yourself asking. “The Freybug isn’t a modern monster, even if it’s obscure. It’s the Norfolk black dog. It got itself a starring role in William O’Connor’s Dracopedia series (which you should review) and even got name-checked as a Hound in Final Fantasy (pictured). It even got its own Wikipedia entry!” You’d be right as usual, good reader. But I would like to draw attention to the dearth of information regarding this Freybug. What is it? Where did it come from? Why was it used in the Dracopedia and Final Fantasy?

It’s all about the name really. Final Fantasy needed another black dog name, and the Dracopedia needed something fancy and frightening for the letter F. Besides, it has the words frey and bug. Two great tastes that taste great together.

As with many obscure creatures, Giants, Monsters, and Dragons is the ultimate source. What does GMaD tell us?

This is the name of a monster in the medieval traditions and folklore of England. It took the form of a monstrous black dog that patrolled the country lanes at night terrifying late travelers and making them flee in horror. It is mentioned in an English manuscript of 1555.

There is only one reference provided, which hilariously is Rose’s other book, Spirits, Fairies, Gnomes, and Goblins. And SFGaG says the following.

This is the name of a demon of the roads in English folk beliefs of the Middle Ages. It was described as a Black Dog fiend and referred to in an English document of 1555.

References? None whatsoever. Dead end. I know I’ve complained about it a lot but I’ll say it again.

Source.

Your.

Damn.

Creatures.

This is the only freybug reference I can consistently find. I have no idea where the Norfolk thing came from, considering Shuck is the Norfolk black dog. And Shuck wouldn’t take well to competition, I’d wager.

As things stand we have only Rose’s word for it that the freybug is from an “English manuscript” from 1555. One that’s conveniently uncited. Unless further evidence surfaces (and I have no doubt Rose has access to all sorts of cool manuscripts) I’m inclined to consider this a Borgesian literary in-joke. And if it is, it certainly would be a modern creature. Quod erat demonsterandum.

Actual pictures of the yeti. From “Secrets of the Gnomes” by Rien Poortvliet and Wil Huygen.