I had the opportunity to reread George MacDonald’s The Princess and Curdie (TPAC for short) and it wasn’t much fun. MacDonald was the precursor to Lewis and Tolkien, and his moralizing is ham-fisted and unsubtle. It’s a sequel to the superior The Princess and the Goblin, one which focuses on the miner boy Curdie. Our Hero is empowered by one of the vanishing few female mystical figures in Christian fantasy (she’s Gandalf or Aslan, if you will); specifically, she gives him the ability to assess souls by shaking hands. Good people have baby hands, bad people’s hands feel like animal paws.

You see where this is going. (*SPOILERS* I guess for the rest of the review) TPAC is drenched with praise for the divine right of kings to rule and disdain for the disgusting greed of the lower classes. Curdie visits a comically evil town where, apparently, people wake up in the morning every day and decide to be bad. He acts like a jerk, destroys the plot to kill the kindly old king, tortures some plebeians at length (so much that it gets uncomfortable) and eventually becomes king himself because – surprise surprise – he has royal blood in him and so is fit to rule. But then he and the princess die without offspring and the unrepentant sinners of the town mine deep enough that everything collapses. Everyone dies. The end!

I didn’t remember any of that. What I remember from reading it as a child was the monsters.

Ohhh, those monsters. Nobody’s quite sure where they come from. In The Princess and the Goblin they’re the descendants of “regular” animals bred by goblins for subterranean life. In TPAC they’re apparently people whose sinful lifestyle transformed them according to their nature, and they’re now making amends for it. I say apparently because it’s mentioned a few times but not really expounded upon. I loved them to bits at any rate and scribbled them all over my school notebooks at the time.

Let’s see what they are, shall we? The images I’ll be sharing here are by Charles Folkard, Helen Stratton, and Dorothy Lathrop, and will be credited accordingly. All quotes are from TPAC.

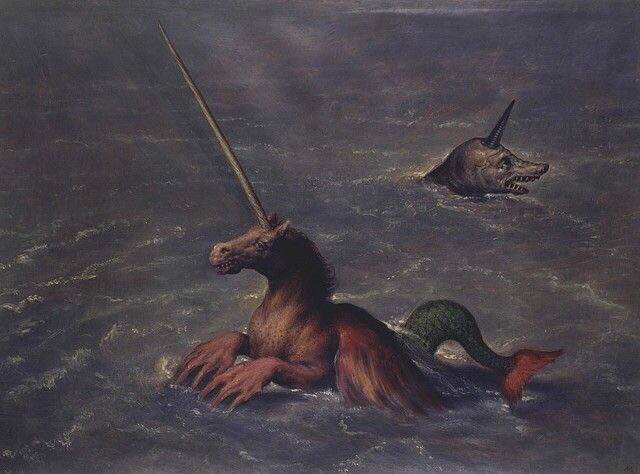

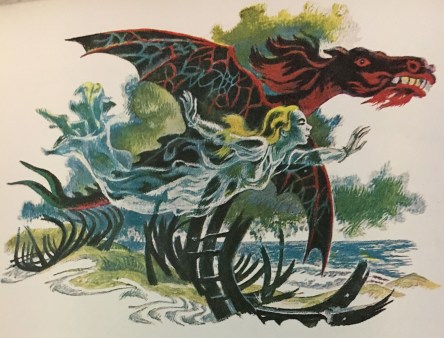

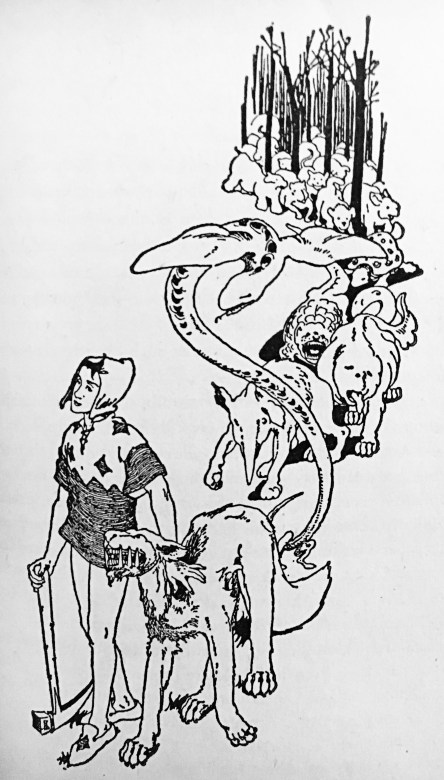

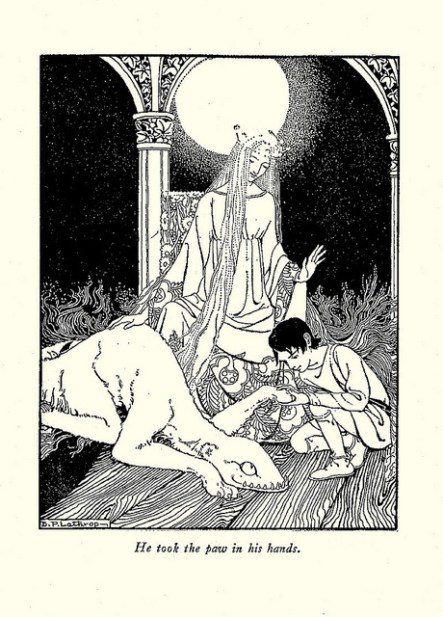

Our first and most notable is the one that accompanies Curdie throughout the book. Her name is Lina, and she is the one in the foreground of the image above by Helen Stratton. Her appearance is striking.

She had a very short body, and very long legs made like an elephant’s, so that in lying down she kneeled with both pairs. Her tail, which dragged on the floor behind her, was twice as long and quite as thick as her body. Her head was something between that of a polar bear and a snake. Her eyes were dark green, with a yellow light in them. Her under teeth came up like a fringe of icicles, only very white, outside of her upper lip. Her throat looked as if the hair had been plucked off. It showed a skin white and smooth.

Of course, Lina accompanies our hero, fights and protects him, and is generally a Good Dog. At the of TPAC she apparently dies happily by incinerating herself in a mass of burning magic roses. Yay?

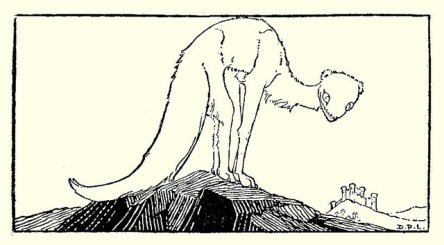

I must admit that Dorothy Lathrop’s version of her (two images above) is adorable.

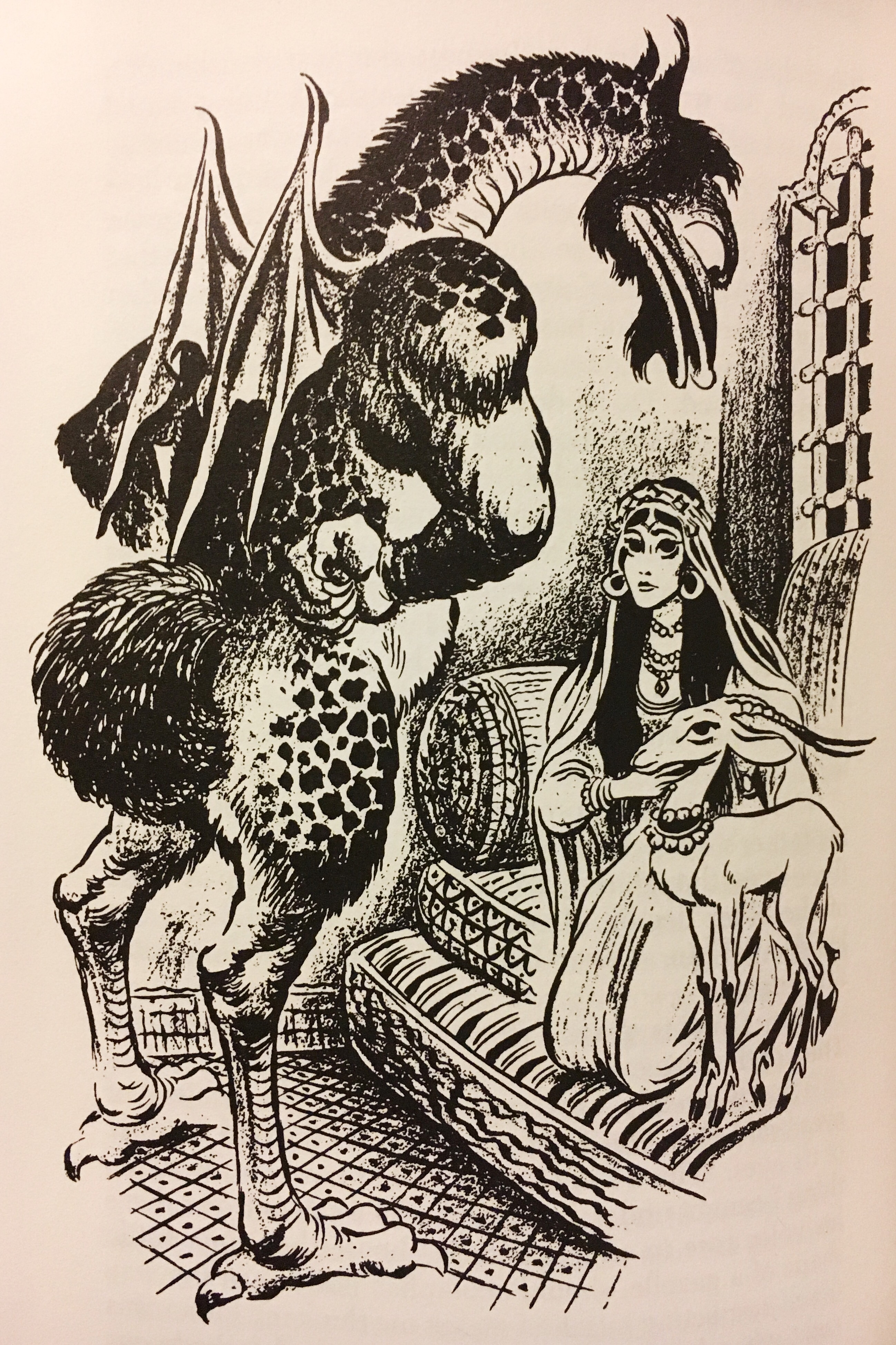

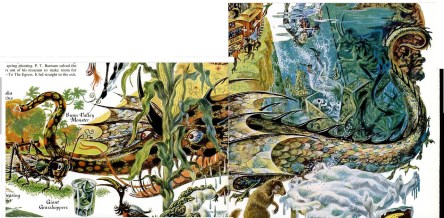

Lina then serves to marshal an army of monsters with which to torment the sinners of the town. Just some of them are shown below in Lathrop’s rendition.

…until at last, before they were out of the wood, she was followed by forty-nine of the most grotesquely ugly, the most extravagantly abnormal animals imagination can conceive. To describe them were a hopeless task. I knew a boy who used to make animals out of heather roots. Wherever he could find four legs, he was pretty sure to find a head and a tail. His beasts were a most comic menagerie, and right fruitful of laughter. But they were not so grotesque and extravagant as Lina and her followers.

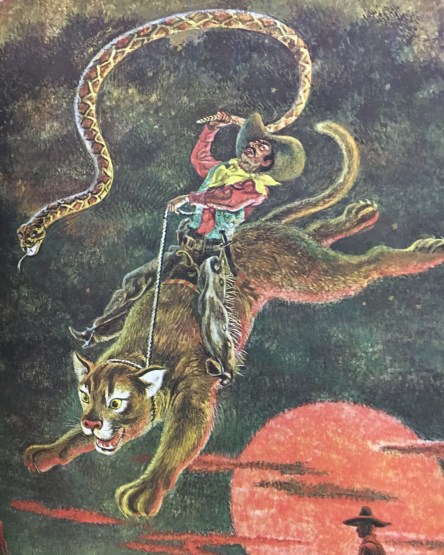

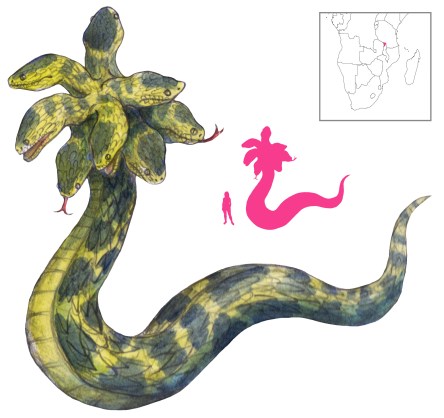

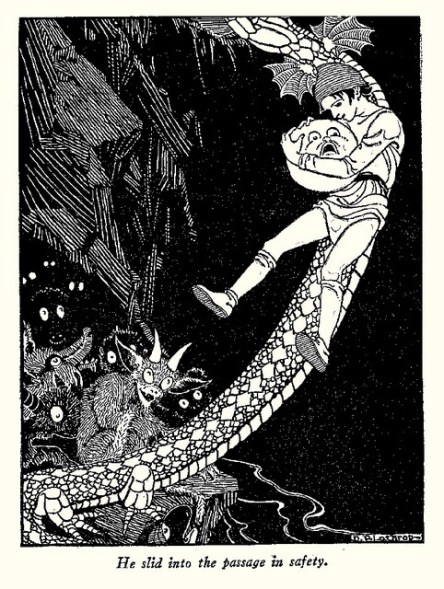

Probably the most memorable of the monsters is the “legserpent”.

One of them, for instance, was like a boa constrictor walking on four little stumpy legs near its tail About the same distance from its head were two little wings, which it was for ever fluttering as if trying to fly with them. Curdie thought it fancied it did fly with them, when it was merely plodding on busily with its four little stumps. How it managed to keep up he could not think, till once when he missed it from the group: the same moment he caught sight of something at a distance plunging at an awful serpentine rate through the trees, and presently, from behind a huge ash, this same creature fell again into the group, quietly waddling along on its four stumps. Watching it after this, he saw that, when it was not able to keep up any longer, and they had all got a little space ahead, it shot into the wood away from the route, and made a great round, serpenting along in huge billows of motion, devouring the ground, undulating awfully, galloping as if it were all legs together, and its four stumps nowhere. In this mad fashion it shot ahead, and, a few minutes after, toddled in again amongst the rest, walking peacefully and somewhat painfully on its few fours.

Imagine Archeops’ desperately flapping wings stapled to a python, and you’re already halfway there.

The legserpent helps Curdie and friends cross a chasm (image above, Dorothy Lathrop), and participates in enacting grisly vengeance on the Lord Chamberlain…

Now his lordship had had a bedstead made for himself, sweetly fashioned of rods of silver gilt: upon it the legserpent found him asleep, and under it he crept. But out he came on the other side, and crept over it next, and again under it, and so over it, under it, over it, five or six times, every time leaving a coil of himself behind him, until he had softly folded all his length about the lord chamberlain and his bed. This done, he set up his head, looking down with curved neck right over his lordship’s, and began to hiss in his face. He woke in terror unspeakable, and would have started up; but the moment he moved, the legserpent drew his coils closer, and closer still, and drew and drew until the quaking traitor heard the joints of his beadstead grinding and gnarring. Presently he persuaded himself that it was only a horrid nightmare, and began to struggle with all his strength to throw it off. Thereupon the legserpent gave his hooked nose such a bite, that his teeth met through it—but it was hardly thicker than the bowl of a spoon; and then the vulture knew that he was in the grasp of his enemy the snake, and yielded. As soon as he was quiet the legserpent began to untwist and retwist, to uncoil and recoil himself, swinging and swaying, knotting and relaxing himself with strangest curves and convolutions, always, however, leaving at least one coil around his victim. At last he undid himself entirely, and crept from the bed. Then first the lord chamberlain discovered that his tormentor had bent and twisted the bedstead, legs and canopy and all, so about him, that he was shut in a silver cage out of which it was impossible for him to find a way. Once more, thinking his enemy was gone, he began to shout for help. But the instant he opened his mouth his keeper darted at him and bit him,and after three or four such essays, with like result, he lay still.

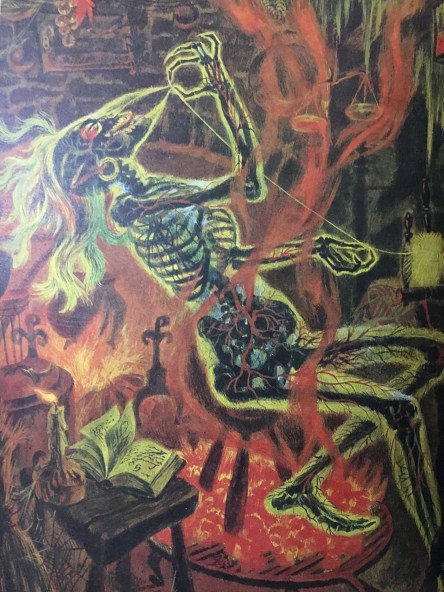

… and the priest on “Religion Day” (image below by Charles Folkard).

At this point of the discourse the head of the legserpent rose from the floor of the temple, towering above the pulpit, above the priest, then curving downwards, with open mouth slowly descended upon him. Horror froze the sermon-pump. He stared upwards aghast. The great teeth of the animal closed upon a mouthful of the sacred vestments, and slowly he lifted the preacher from the pulpit, like a handful of linen from a wash-tub, and, on his four solemn stumps, bore him out of the temple, dangling aloft from his jaws.

Then there’s a whole bunch of other absurdly adorable monstrosities which barely get time to shine. There’s a Scorpion the size of a giant crab, and a three-foot-long Centipede. The sharp-nosed “tapir” and “Clubhead” work in tandem to destroy a rock wall…

At the very first blow came a splash from the water beneath, but ere he could heave a third, a creature like a tapir, only that the grasping point of its proboscis was hard as the steel of Curdie’s hammer, pushed him gently aside, making room for another creature, with a head like a great club, which it began banging upon the floor with terrible force and noise. After about a minute of this battery, the tapir came up again, shoved Clubhead aside, and putting its own head into the hole began gnawing at the sides of it with the finger of its nose, in such a fashion that the fragments fell in a continuous gravelly shower into the water. In a few minutes the opening was large enough for the biggest creature amongst them to get through it.

The tapir puts its nose to gruesome use.

The tapir had the big footman in charge: the fellow stood stock-still, and let the beast come up to him, then put out his finger and playfully patted his nose. The tapir gave the nose a little twist, and the finger lay on the floor. Then indeed the footman ran, and did more than run, but nobody heeded his cries. […] The master of the horse Curdie gave in charge to the tapir. When the soldier saw him enter—for he was not yet asleep—he sprang from his bed, and flew at him with his sword. But the creature’s hide was invulnerable to his blows, and he pecked at his legs with his proboscis until he jumped into bed again, groaning, and covered himself up; after which the tapir contented himself with now and then paying a visit to his toes.

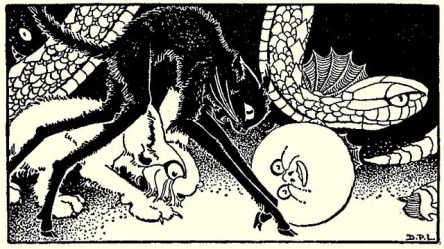

“Ballbody” is probably the silliest.

…he had neither legs nor head nor arms nor tail: he was just a round thing, about a foot in diameter, with a nose and mouth and eyes on one side of the ball. He had made his journey by rolling as swiftly as the fleetest of them could run. […] …he could do nothing at cleaning, for the more he rolled, the more he spread the dirt. Curdie was curious to know what he had been, and how he had come to be such as he was; but he could only conjecture that he was a gluttonous alderman whom nature had treated homœopathically.

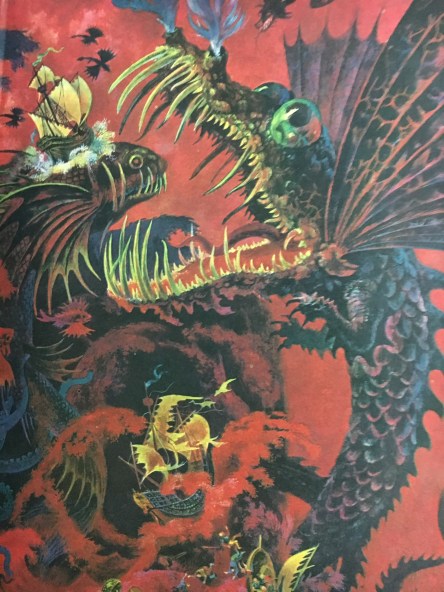

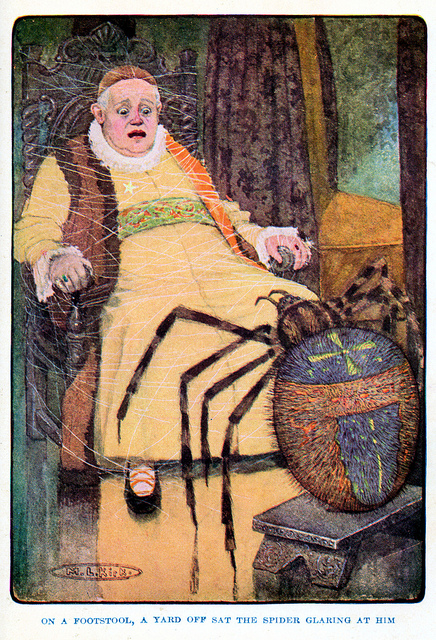

And then there’s the giant spider, which inspired at least two pieces of art, first by Charles Folkard.

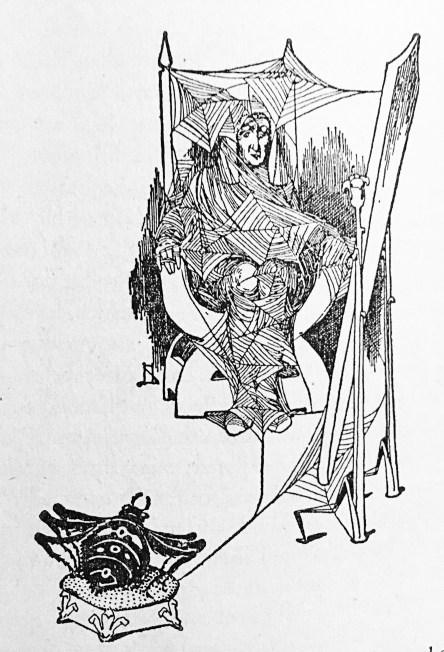

For the attorney-general, Curdie led to his door a huge spider, about two feet long in the body, which, having made an excellent supper, was full of webbing. The attorney-general had not gone to bed, but sat in a chair asleep before a great mirror. He had been trying the effect of a diamond star which he had that morning taken from the jewel-room. When he woke he fancied himself paralysed; every limb, every finger even, was motionless: coils and coils of broad spider-ribbon bandaged his members to his body, and all to the chair. In the glass he saw himself wound about, under and over and around, with slavery infinite. On a footstool a yard off sat the spider glaring at him.

And then by Helen Stratton. I cannot properly express how much I love the above image. You can just imagine the spider glaring crossly at the poor guy, all like òÒÓó

Well, that concludes our retrospective through MacDonald’s lovingly designed monstrosities. If TPAC had been only about their adventures it would probably have been far more fun.