Variations: Aspic, Aspis, Egyptian Asp, Egyptian Cobra, Egyptian Viper, Aspic Viper, Chersaiai, Chelidoniai, Hypnalis, Ptuades; Akschub, Pethen, Zipheoni (Hebrew); Plasyos, Hascos (Arabic); Aspe, Aspide (Italian); Bivora (Spanish); Schlang Gennant (German)

The Asp was the first snake to be born from Medusa’s blood, and it has the most poison in its body of any snake. As such it has garnered a fearsome reputation in classical sources. When speaking of the asp it is important to differentiate between the Egyptian cobra, the aspic viper, and the asp of legend, which is both and more besides. It is never clear exactly what the asp in ancient literature is supposed to be; indeed, it is best regarded as a composite of all that was feared in venomous snakes.

According to Topsell’s reference to Aristophanes, the name is derived from an intensive of spizo, “to extend”. It is also the name of a shield, an island in the Lycian Sea, and an African mountain, among other things.

Lucan gives the asp pride of place in his catalogue of snakes, but it is not described killing in gruesome detail. The reference to a “crest” and a “swelling neck” suggests a cobra.

Nicander says that the asp can grow up to a fathom (about 1.8 meters) long. It has four fangs and two tuloi (“cushions” or “mats”) over its forehead. It rears its body up from a coiled position, and its bite causes painless death.

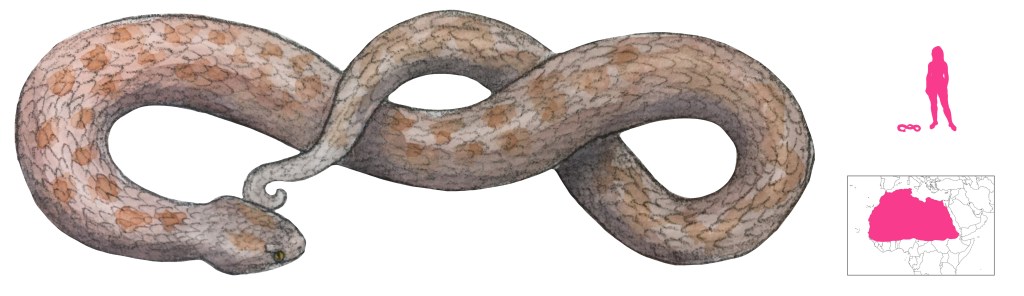

Philoumenos specifies three types of asp. The chersaiai (“terrestrial”), Egyptian asp, or Egyptian cobra is 3 to 4 cubits long and pale grey, black, or red in color. There are three rows of black-bordered rufous spots on its back that join to form a zigzag band towards the tail. The chelidoniai (“swallow-colored”), asp viper, or water asp is smaller, 1 cubit in length, mottled with chestnut markings on a light brown background. There are reddish stripes on the head. The ptuades (“spitters”) or spitting cobras are 3 feet long and are grey, green, or gold in color. To that may be added the Hypnalis, so called because it sends its victims to eternal sleep.

Asps themselves are preyed upon by ichneumons, who coat themselves in an armor of dried mud. The asp can still win the battle by biting the unprotected nose. Ichneumons also eat asp eggs.

Asps are highly common in Egypt, and are regarded as the sacred snake of the Pharaohs. Pharaonic crowns show the asp to represent the king’s power. It is likely this is the snake Cleopatra used to kill herself.

The primary reference to the asp in Christian symbolism is Psalm 58. Asps have poor eyesight and will stop up their ears to avoid being charmed. To prevent themselves from hearing the music of charmers they close one ear with their tail and press the other to the ground. Thus they represent those who reject the message of God by stopping up their ears.

Not all asps are irredeemably bad. One female asp fell in love with an Egyptian boy, warning him of danger and keeping watch over him.

While very venomous, asp bites are sometimes nonlethal. The venom spreads rapidly to the core of the body. Typical symptoms include suffocation, convulsions, and retching. It can cause blindness by breathing in a victim’s eyes.

Aelian believed the bite of the asp to be beyond curing. He also contradicts himself by saying that the asp’s bite can be cured through excision or cautery. Pompeius Rufus supposedly tried to prove that an asp’s venom could be sucked out and neutralized, and had an asp bite him on the arm to make his point. He died because someone took away the water he would have used to rinse out his mouth.

Topsell denied allegations that asp bites were incurable. He suggests cutting into the flesh at the bite and drawing out the venom with cupping-glasses or reeds. Rue, centaury, myrrh, and sorrel, opium, butter, yew leaves, treacle and salt, induced vomiting, garlic and stale ale, aniseed, and a number of other remedies are prescribed.

As with all snakes, asps are frequently given legs and dragon’s features in medieval illustrations. A creature with its ear stopped up is unquestionably an asp. In Romanesque sculpture it appears as a dragon with a crest or mane; the asp from the Saint-Sauveur church of Nevers is a sort of six-legged lizard with a flattened head and a mane running the length of its body.

References

Aelian, trans. Scholfield, A. F. (1959) On the Characteristics of Animals, vol. I. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Aelian, trans. Scholfield, A. F. (1959) On the Characteristics of Animals, vol. II. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Aldrovandi, U. (1640) Serpentum, et Draconum Historiae. Antonij Bernie, Bologna.

Anfray, M. (1951) L’architecture religieuse du Nivernais au Moyen Age. Editions A. et J. Picard et Cie., Paris.

Braun, S. (2003) Le Symbolisme du Bestiaire Médiéval Sculpté. Dossier de l’art hors-série no. 103, Editions Faton, Dijon.

Druce, G. C. (1914) Animals in English Wood Carving. The Third Annual Volume of the Walpole Society, pp. 57-73.

Hippeau, C. (1852) Le Bestiaire Divin de Guillaume, Clerc de Normandie. A. Hardel, Caen.

Kitchell, K. F. (2014) Animals in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon.

Macloc, J. (1820) A Natural History of all the Most Remarkable Quadrupeds, Birds, Fishes, Serpents, Reptiles, and Insects in the Known World. Dean and Munday, London.

Robin, P. A. (1936) Animal Lore in English Literature. John Murray, London.

Topsell, E. (1658) The History of Serpents. E. Cotes, London.

Is this the last Ethiopian serpent?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps. Perhaps not. Who can say for sure?

(It’s not, there are always more 🐍)

LikeLike

Hi!

Just a little comment about this post: in Spanish we say “Víbora” instead of “Bivora”

By the way, you ar doing an excellent job!

Best regards from Barcelona 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! Thank you but I’m copying those right out of Topsell and he makes those mistakes, but I should probably have specified that 😛

LikeLiked by 1 person

Medieval Illustrators: “Anybody else want legs?”

*snakes cower in terror*

LikeLiked by 2 people

Actually it’s kinda crazy you chose this week to showcase the Asp, I’m currently trying to draw a concept the Python of Delphi for an Apollo and Daphne illustration project of mine. It truly is the week of the snakes!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hey, snakes are scary!

LikeLiked by 1 person

And what better way to convey scariness than legs?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Where did you get the cat-like depiction with six legs?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Right here!

Braun, S. (2003) Le Symbolisme du Bestiaire Médiéval Sculpté. Dossier de l’art hors-série no. 103, Editions Faton, Dijon.

LikeLike